blog

Isolation in ACID Transactions

10th Sep 2020

In 1981, Jim Gray¹ published the paper, The Transaction Concept: Virtues and Limitations, in which he provides the following definition of a transaction:

"A transaction is a transformation of state which has the properties of atomicity (all or nothing), durability (effects survive failures) and consistency (a correct transformation)."

This paper introduced the A, C and D of ACID transactions that we are familiar with today. Two years later, in 1983, Theo Härder and Andreas Reuter² published a paper titled Principles of Transaction-Oriented Database Recovery which explained that allowing multiple users to manipulate data concurrently can introduce undesired behavior. The following conveys an example of possible undesired behavior that may arise as a result of the concurrent manipulation of data.

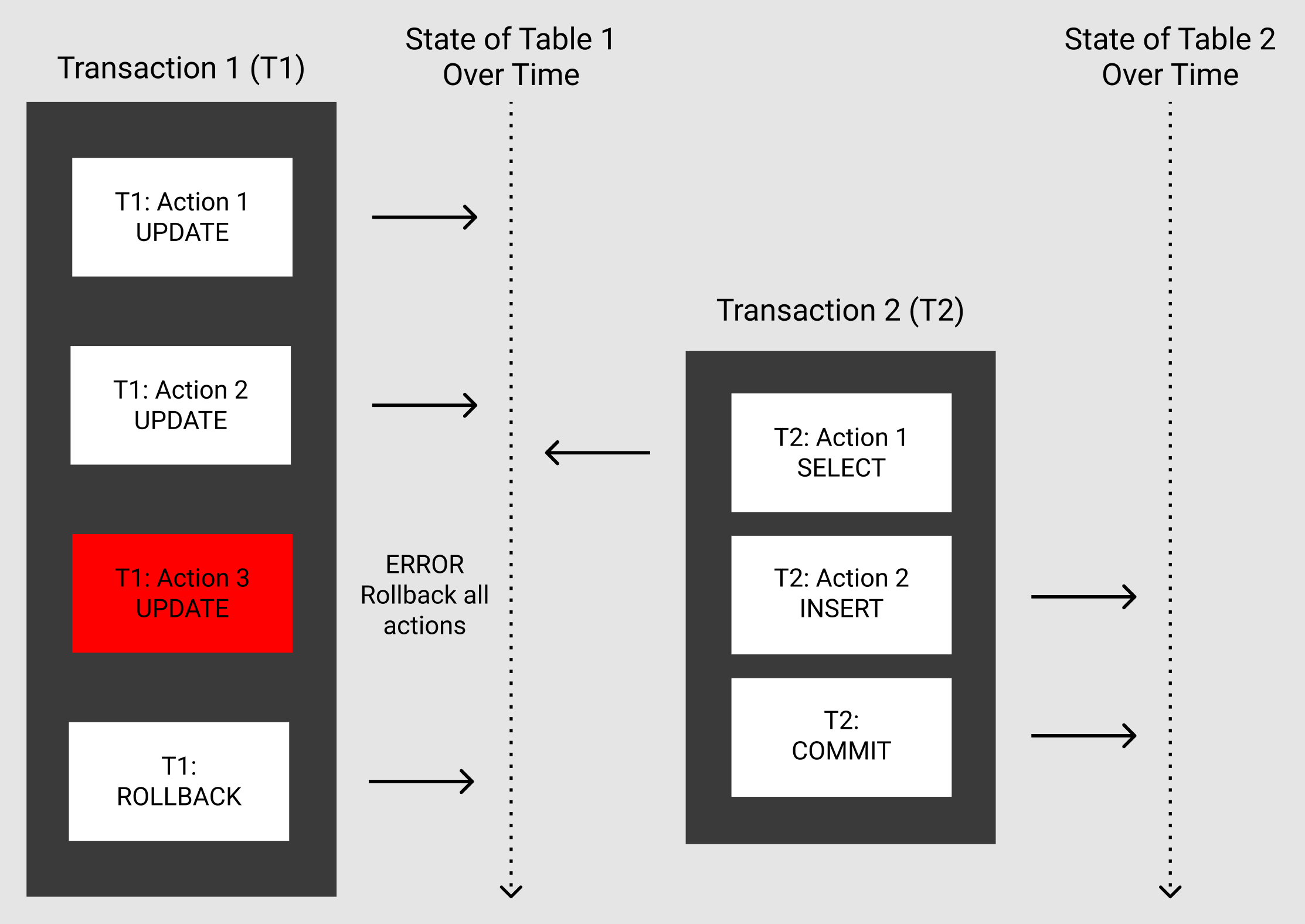

Consider a fictional DBMS that has no concept of isolation. A user executes a transaction (T1) that consists of 3 UPDATE statements to existing data. Statements 1 and 2 complete successfully, updating some integer values in Table 1. At this point, another transaction (T2) reads this newly updated data from Table 1, inserts this into Table 2, and commits the transaction. T1 now executes its 3rd action and notices that the UPDATE statement is trying to change a primary key to a value that already exists in the table, thus violating a constraint. As explained by the atomic property of the ACD transactions introduced by Gray, this action should not complete, and actions 1 and 2 should be rolled back. T1 successfully rolls back it's actions, leaving Table 1 in the same state it was at the beginning of the transaction. However, Table 2 now contains data that has been read from Table 1 after T1's 2nd UPDATE statement, which has since been rolled back, thus leaving the data in an inconsistent state.

As a result of this, Härder and Reuter proposed that transactions should also be Isolated, as well as Atomic, Consistent and Durable, providing us with the concept of ACID that we know today. In this blog post, I will go into detail about the Isolation property of ACID transactions and why it is so important.

Indivisibility

Härder and Reuter propose that a sequence of actions can only be described as a transaction if the actions are executed indivisibly, as described below.

"The concept of a transaction . . . requires that all of its actions be executed indivisibly: Either all actions are properly reflected in the database or nothing has happened."

From this quote, we can understand that a transaction should have only two possible outcomes:

- All actions within the transaction complete successfully.

- The transaction has no effect.

They then go on to describe that a sequence of actions can be indivisible only if it follows the four ACID principles. At first, this statement may not seem obvious. The concept of indivisibility is closely related to atomicity, so it is easy to assume that atomicity alone provides a sequence of actions with indivisibility. This is not the case. As shown in the previous example, T2 reads data from Table 1 which has previously been updated, but not committed, by T1. T2 then inserts this data into Table 2 and commits, before T1 encounters an error and has to rollback. By the previous definition of indivisibility, T1 did not complete successfully and therefore should have had no effect at all. This was not the case as T1 has had an effect on the data inserted into Table 2 by T2, showing that each sequence of actions is not indivisible due to the lack of isolation.

Isolation

Härder and Reuter describe Isolation as:

"Events within a transaction must be hidden from other transactions running concurrently."

The main invariant of perfectly isolated transactions is that the concurrent execution of multiple transactions should have the same result as if the transactions were executed in some serial order. This is called serializability. Using read/write locks on a range level with two-phase locking (2PL) is often used to achieve this. This post will not cover this in detail, however it is useful to understand that this process alone guarantees serializability.

When transactions are fully serializable, the level of possible concurrency is reduced due to the amount of locking used. For this reason, the level of isolation used in database transactions tends to be reduced depending on the use case, providing a tradeoff between perfect isolation and concurrency.

Isolation Phenomena

The SQL-92 standard defines three phenomena that can occur when transactions are not fully isolated. The examples here consider two transactions, T1 and T2.

- Dirty Read: T1 reads a change that has been made, but not yet committed, by T2.

- Non-Repeatable Read: T1 initially reads some data. This is then updated by T2 and the transaction is committed. T1 reads this same data again and sees the updates made by T2.

- Phantom Read: T1 reads some data based on a search condition. T2 inserts new data that falls within the same search condition and commits the changes. T1 then reads data based on the same search condition and sees the new data inserted by T2. This new data is described as the phantom data.

Levels of Isolation

There are 4 isolation levels defined by the SQL-92 standard. Whether or not each of the phenomena previously described arise depends on which level of isolation is used. These levels of isolation are presented below in order of most isolated (1) to least isolated (4).

- Serializable: To say that transactions are serializable, the concurrent execution of multiple transactions should produce the same result as some serial execution of these transactions, which is typically achieved using read/write locks on ranges of data with 2PL. This prevents Dirty Reads, Non-Repeatable Reads and Phantom Reads.

- Repeatable Read: With this level of isolation, Dirty Reads and Non-Repeatable reads are prevented, but Phantom Reads are allowed. Range locks are not used here, so if new data is inserted by T2 which meets the search criteria of a statement in T1, a second read will see the new data.

- Read Committed: This level of isolation maintains write-locks throughout the transaction, however read-locks are dropped as soon as the read is completed. If T1 is finished reading some data, it will drop the lock on this data. T2 can then obtain a write-lock on this same data, update it, and commit the results, which would drop the write-lock. Once T1 reads this data again, it will see the changes made by T2. Therefore, this level of isolation allows both Non-Repeatable Reads and Phantom Reads.

- Read Uncommitted: This allows transactions to read data that has been updated, but not yet committed, by other transactions, which is known as a Dirty Read. Both Non-Repeatable Reads and Phantom Reads are also allowed at this isolation level.

Which of these you use with your DBMS depends completely on the use case. If you would like to learn more, I would highly recommend the content included in the bibliography section below.

Bibliography

- J. Gray, The transaction concept: virtues and limitations. 1981

- T. Härder and A. Reuter, Principles of transaction-oriented database recovery. ACM Comput. Surv. 15, 1983