blog

The Cascading Failure Problem

4th Oct 2020

Doug McIlroy is well renowned for being the innovator behind Unix pipelines, along with his work on a range of programming languages and Unix programs. In 1978 while working at Bell Labs, McIlroy noted down a list of principles in the Bell System Technical Journal that characterized the style of the Unix programs being developed at the time. The first of his principles was later simplified into what has become an adage in the Unix community:

"Write programs that do one thing and do it well."

This principle is woven throughout Unix, and has become a common practice in many other areas of software engineering. In the early 2000s, the adoption of this philosophy in the world of web application architecture sparked the introduction of microservices. Architecting web applications as sets of loosely coupled services allows for increased scalability, faster deployability, higher maintainability and a large range of other benefits. However, the adoption of microservices does introduce its own challenges.

Cascading Failures

One of these challenges is the cascading failure problem. This is where the failure of one component in a software system can cause one to many other components to fail. In this day and age, we take great pride in the low coupling and high cohesion of our systems, but can we really say our services are truly decoupled if the failure of one can cascade to others?

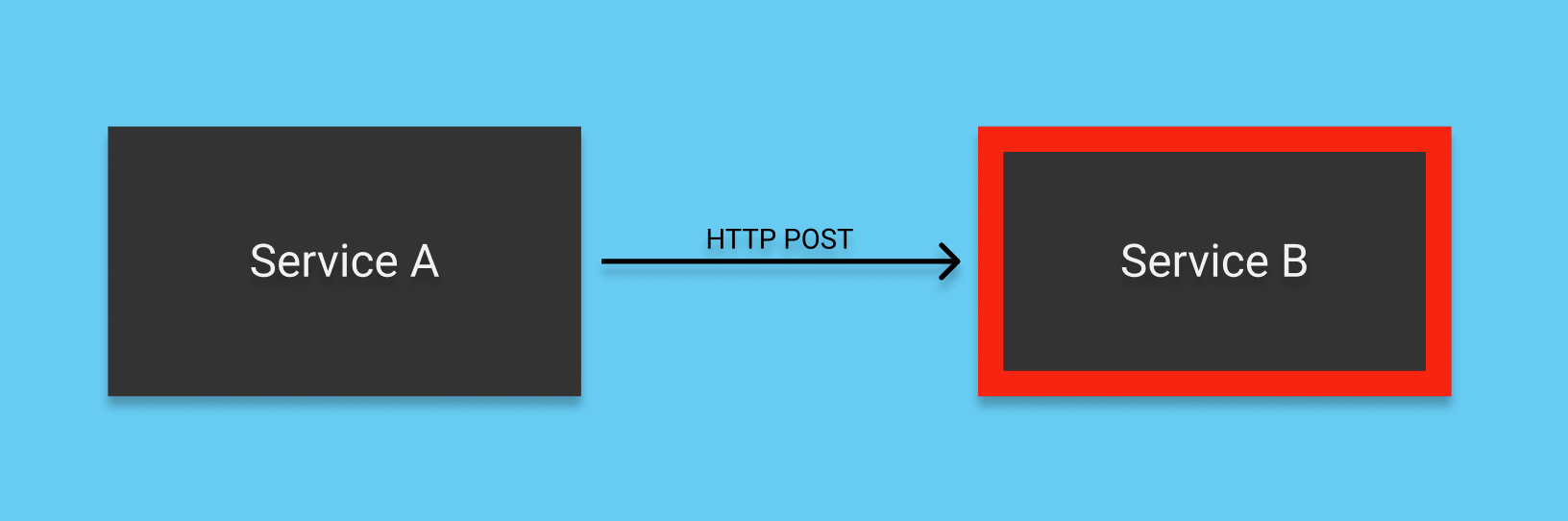

The following explains the simplest example of how a failure can cascade in a microservice architecture. Consider the case where a service A is periodically making synchronous HTTP POST requests to a service B, as shown in the diagram below. During normal operation, service to service communication is working as expected and requests in this architecture generally receive responses quickly. Service B then experiences a problem which is causing all incoming requests to hang and eventually timeout, as shown below in red. Service A has no way of handling this, and so it blocks and waits for a response.

Over time, the number of active threads waiting for responses on service A builds up and eventually tends towards the limit available on the particular web server being used. Service A may have many other responsibilities which it is now unable to carry out, as all of its resources are consumed waiting on responses from B. This simple example shows how the failure of one service can cascade to another.

If we scale this up and consider now that service A has many clients, we can imagine how the impact of this failure can cascade even further. When any client now makes a synchronous request to service A, the request will hang as there are no resources available to handle it. This will eventually lead to a lack of available resources on the clients of service A, causing them to also be negatively impacted. This cascading effect can continue spreading through the architecture unless a solution is implemented that will constraint the effects of failures to only directly impacted services.

Circuit Breakers

Thankfully, many people have done a significant amount of work researching and writing about reliable communication mechanisms in the world of microservices. I first read about circuit breakers in Chris Richardson's¹ great book, Microservices Patterns. Michael Nygard² also described this in his book Release It, and Martin Fowler³ also covered this topic on his blog. In this section, I will describe the implementation of circuit breakers shown by Martin Fowler.

A circuit breaker is a component that monitors a particular function call for failures, and if the number of failures reaches a certain threshold, the circuit breaker will not allow any other invocations of this function call, responding instead with a default response or an error. When working with microservices, the function calls that make use of this technique are usually HTTP requests to other services. The circuit breaker explained below deals specifically with timeouts and does not consider the time period in which the errors occurred.

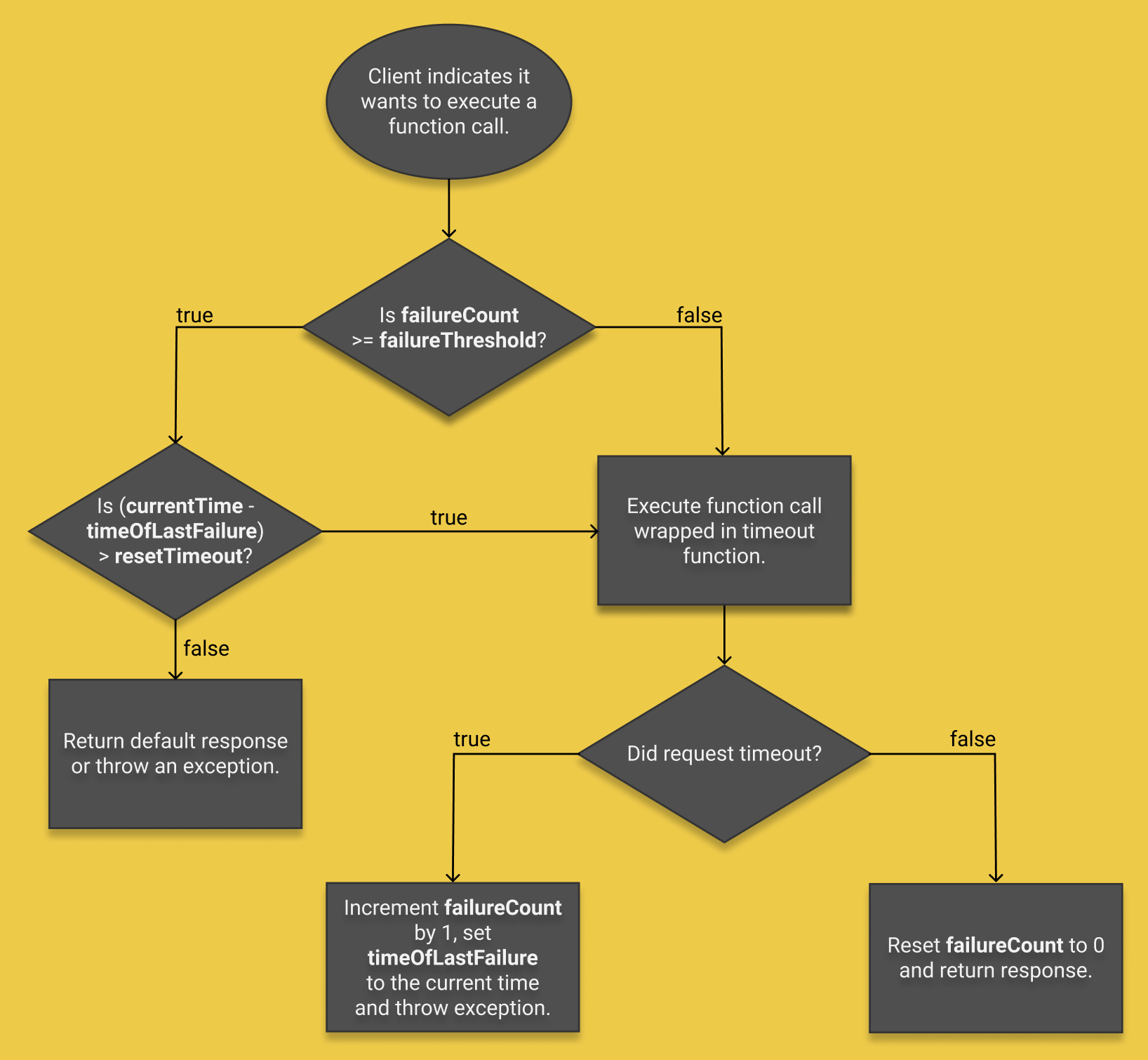

When a function call is made, the circuit breaker first checks whether the failureCount has reached the failureThreshold. If not, the function call is executed and the timeout function monitors the time it takes. If this duration exceeds the timeout duration, the failureCount is incremented by 1, the timeOfLastFailure is set to the current time and an exception is thrown. If not, this means the request was successful, so the failureCount is reset to 0 and the response is returned. When the failureCount does reach the failureThreshold, then a default response is returned or an exception is thrown. However, before doing this, the circuit breaker should also check how long it has been since the last failed call was made. If this duration exceeds the resetTimeout, then an attempt should be made to send the request, in case the issue has been resolved. If the request succeeds, the failureCount is reset to 0 and the response is returned. If not, the failureCount is incremented by 1, the timeOfLastFailure is set to the current time and an exception is thrown.

Going back to the previous example, the cascading effect caused by the failure of B could be avoided by simply adding a circuit breaker to service A's call to service B. As all of the requests to service B time out, the failureCount would eventually exceed the failureThreshold, and the circuit would open. The circuit breaker would then stop service A from being able to send any requests to service B for a period of time, and would instead respond with either a default response or an error. As a result, service A would have resources available to carry out its other responsibilities and handle any requests from its clients, allowing this part of the system to function as normal.

Designing reliable communication mechanisms in today's microservices world is an extremely important factor in having a highly available system. The use of circuit breakers is only one of many methods used to help achieve this. For further reading on this topic, please check out the resources in the bibliography below.

Bibliography

- C. Richardson, Microservices. 2018, p. 78.

- M. T. Nygard, Release It! Design and Deploy Production-ready Software. 2007.

- M. Fowler, CircuitBreaker. 2014 [Online]. Available: https://martinfowler.com/bliki/CircuitBreaker.html